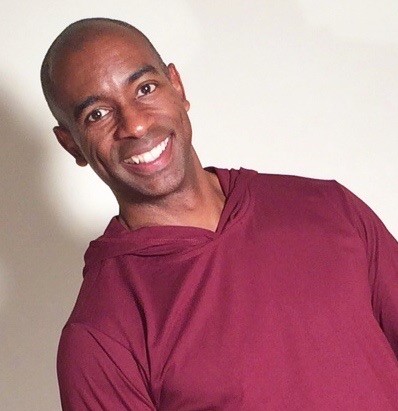

This article has been reviewed for accuracy by John Cottrell, Ph.D. in Clinical Psychology . Medical Disclaimer: The information and recommendations on our site do not constitute a medical consultation. See a certified medical professional for diagnosis.

. Medical Disclaimer: The information and recommendations on our site do not constitute a medical consultation. See a certified medical professional for diagnosis.

Generally, close physical contact between a therapist and a client is frowned upon because it can blur boundaries, send the wrong message, be self-serving for the practitioner, negatively affect some clients, among other reasons. But can a hug, a widely accepted “normal” greeting, be that bad for a therapeutic relationship?

Technically, a therapist could hug a client, which is not considered unethical by the American Psychological Association (APA). However, practitioners need to use the APA’s general principles to evaluate physical contact’s potential impact on both the client and the therapeutic relationship.

Read on for more on the APA code’s standing on therapists hugging their clients and a conclusive bottom line on the subject.

At Safe Sleep Systems, we’re supported by our audience, and we thank you. As a BetterHelp affiliate, we may receive compensation from BetterHelp if you purchase products or services through the links provided, at no additional cost to you. Learn more .

.

The Ethics of Hugging in Therapy

Hugging is recognized as a form of touch in therapy. Thus, whether it’s ethical for a therapist to hug a client depends on the ethicality of touch in therapeutic relationships. As with many other ethical considerations in therapy, this is dependent on the guidelines outlined by the American Psychological Association (APA) ethics code.

To establish whether it’s unethical to get a hug from your therapist, let’s examine the question against the APA ethics code.

Put bluntly, a therapist’s ethicality hugging a client is somewhat a grey area because it’s not explicitly addressed in the APA ethics code. It’s not the only issue that the ethics code fails to address, too, with things like accepting gifts from clients and other forms of touching such as a pat on the back or holding hands not explicitly prohibited.

Thus, it’s up to the therapist to decide when it’s ideal for hugging you based on the context and their theoretical orientation. More often than not, this presents a challenging ethical dilemma for the practitioner. To make the right call, they need to evaluate the potential implications of hugging you against the APA code’s general principles. The most relevant ones to this decision include:

- The principle of beneficence and nonmaleficence

- The principle of integrity

- The principles of fidelity and responsibility

- The principle of respect for people’s rights and dignity

Let’s discuss each principle’s ethical implications on a therapist’s decision to hug a client in the next section.

The Principle of Beneficence and Nonmaleficence

This principle urges therapists not to harm and only to use interventions that’ll likely benefit their clients. Since hugging and other forms of touch can be very emotional, it may trigger positive and negative feelings in a client, depending on their psychological state. For instance, former abuse/violence victims or individuals with paranoid/borderline personality traits may perceive touch as threatening or intrusive.

Given the potential impact of touch on various clients, a therapist should only hug you if they know you very well and are confident that doing so won’t hinder your progress. Even then, they need to seek your consent beforehand.

Consent can be verbal or written, but the latter form is almost always mandatory when a touch is a primary tool in therapy sessions. If your therapist only wants to use hugging and other forms of physical contact every once in a while to supplement verbal psychotherapy (such as to show empathy during an emotional session), verbal consent will suffice.

While on the subject of consent in therapeutic relationships, it’s worth mentioning that your therapist needs to make you feel comfortable declining their request to hug or touch you in any other way.

They need to assure you that they won’t get offended by your response and that your therapeutic relationship will remain intact even if you say no to their advances to hug you. They also need to clarify that you can always change your mind whenever you don’t feel comfortable with any form of touch, including hugging.

The Principle of Integrity

This principle is all about therapists treating their clients with utmost honesty and transparency. In the context of today’s discussion, the implication is that it’s unethical for a therapist to decline your request for a hug purely out of fear of facing scrutiny from regulatory organizations. If there are other underlying reasons for them declining your advances for a hug (like when they detect sexual undertones), your therapist should clearly explain their reservations.

To demonstrate why this is important, think of an individual living with HIV who goes in for a hug, only to be turned down because their therapist is afraid that hugging may amount to an ethical violation.

This person is likely struggling with the stigma HIV/AIDS often poses, only to realize that the one person they thought could help them tackle the issue treats them just like everyone else. Worse still, the therapist fails to explain why they turned down their hug, further validating the stigma.

See how that can be detrimental to a client’s recovery?

On the other hand, you are not entitled to a hug from your therapist just because you request it. The decision should be mutual. If your therapist turns down your hug and you feel you deserve an explanation, take this opportunity to have an honest discussion about your therapeutic relationships’ boundaries.

The Principles of Fidelity and Responsibility

These two principles further reinforce the importance of therapists acting in their clients’ best interests. Typically, therapeutic relationships are characterized by a power imbalance, where the therapist holds more power than the patient. With this power comes an inherent risk of clients accepting whatever their therapist suggests even when they’re not entirely comfortable with the suggestion.

This risk is one of the primary sources of reservations towards the use of hugs and other forms of touch in psychotherapy because it puts therapists in a position to use their power for exploitive purposes. That’s why each therapist needs to weigh the decision to hug a client against APA’s general principles of fidelity and responsibility.

It’s the therapist’s responsibility to use their persuasive power in a manner that benefits you as the client. This is particularly crucial when the practitioner is open to the idea of hugging, but they aren’t sure whether your consent means that you don’t mind that form of touch. The implication here is that the practitioner should only hug you when your therapeutic relationship has developed well enough for them to understand two key things:

- Your history, especially your previous experiences of hugging and other forms of touch.

- Your non-verbal cues, so they know when your “yes” means “no.”

The Principle of Respect for Other People’s Rights and Dignity

This principle demands that a therapist takes the initiative to understand what touch means from the perspective of the client’s personality, gender, and culture before they introduce it to the therapeutic relationship. The rationale is that hugging qualifies as nonverbal communication and can easily be misinterpreted if the practitioner and the client aren’t on the same page regarding its meaning.

For instance, men generally tend to interpret hugging and other types of close physical contact as sexual. They’re also less likely to initiate nonsexual touch than women. Thus, a man is more likely to experience a hug as a sexual overture than a woman, meaning that a therapist dealing with male clients runs a higher risk of having their hug misinterpreted.

Similarly, personal and ethnic differences in what qualifies as casual touch can lead to an otherwise innocent hug by a therapist being misinterpreted. So before going in for one, a therapist needs to talk to you about your cultural and personal orientation towards the touch and possibly document how you feel about it.

The Bottom Line

To summarize everything we’ve covered, here’s the key takeaway: It’s not unethical for a therapist to hug their client provided that kind of physical contact isn’t exploitative, misinterpreted by either party, or getting in the way of progress.

Ultimately, it’s up to you to decide whether your therapist can hug you. If you prefer not to have any form of physical contact with your therapist, online platforms like Blahtherapy and its alternatives may be a better fit for your needs. With these, you can get your therapy fix without having to deal with anyone in-person.

John Cottrell, Ph.D., is a yoga instructor and certified yoga therapist in Salt Lake City, Utah, USA. He has been teaching yoga since 2000. John is originally from Oakland, California, earning his Master of Science and Ph.D. from Pacific Graduate School of Psychology in Palo Alto, California. His clinical practice led him to child and adolescent psychotherapy, drug and alcohol treatment, psychological and neuropsychological testing, and group/couples therapy. John continues his devotion to sharing health and well-being through his business, mbody. He offers private and group yoga classes, yoga therapy, workshops, retreats, written yoga articles, and a men’s yoga clothing line.

Sources

- Counseling Today: The healing language of appropriate touch – Counseling Today

- Quora: Can I give my therapist a hug?

- Vladimir Musicki: Hugs in psychotherapy: Good or bad thing? – Vladimir Mušicki, PhD

- Researchgate: (PDF) Multiple relationships and professional boundaries

- APA: Ethical principles of psychologists and code of conduct

- Zurinstitute: To Touch or Not to Touch: Clinical and Ethical Considerations in Nonsexual Touch in Psychotherapy